EXIT NOW

24 HOUR HELPLINE: 0808 2000 247

020 8539 0427

Because of Ashiana, I can imagine my future

An interim evaluation of Ashiana Network’s National Lottery Community Fund provision Imkaan, December 2019

The interim evaluation was led by Lia Latchford with support with data collection from Neha Kagal, editorial support and oversight from Sumanta Roy and support with report design from Ikamara Larasi.

We thank all Ashiana staff and stakeholders who took the time to share their insight and expertise with us and we give particular thanks to Bushra Ekrem and Shaminder Ubhi for their ongoing guidance and support throughout the evaluation. We would like to acknowledge the women who have accessed Ashiana for assistance and whose stories of survival, resilience and hope were threaded through direct interviews and in our analysis of cases.

Ashiana Network is a multi-award-winning community-based project first established in 1989 as part of the Waltham Forest Young People’s Housing Project, which housed young homeless people. It grew from a need for safe housing for young south Asian women who were experiencing familial domestic violence and began as a seven-bed house with resettlement support, becoming an independent charity in 1994. It has since expanded to provide a range of services for Black and minoritised women and girls and is nationally recognised as a high-quality ending violence against women and girls (VAWG) organisation, with accreditation through Women’s Aid National Standards and Imkaan’s Accredited Quality Standards (IAQS). The organisation works from a feminist, rights-based approach under the premise that VAWG is gender-based violence and that everyone has the right to live a life free of oppression, fear and violence.

Ashiana’s mission is to empower Black, ‘minority ethnic’ (BME) and refugee women, particularly South Asian, Turkish and Iranian women subject to VAWG through culturally sensitive, confidential, person-centred advice, support and safe housing.

In 2015, Ashiana applied to the Big Lottery Fund, now named the National Lottery Community Fund (NLCF), Women and Girls Initiative after funding from the London Borough of Waltham Forest was redirected away from their service. It was envisaged that the funding would support Ashiana to sustain and develop existing specialist provision to meet increasing demand and support new groups of women from Middle Eastern countries, particularly known conflict zones. The successful application was to provide ‘a specialist bespoke refuge, advice and counselling service for BME women survivors of VAWG and, in particular, women fleeing conflict zones’ which is part-funded by the NLCF from July 2016 to June 2021. The NLCF funds one full-time post in Ashiana’s advice, counselling and refuge services, specifically:

A Senior Specialist Advice Worker to support 250 Black and minoritised women and girls per year, aged 16 and above, assessed as ‘low’ or ‘medium’ risk through specialist one-off advice and short to long-term casework This includes ongoing safety planning, risk assessment, intensive advocacy, provision of information and linking women and girls to additional support - alongside responsibility for the day-to-day running of the team, allocating referrals, responding to high risk cases in line with Ashiana’s safeguarding processes and providing peer support to other members of the team.

A Senior Housing Support Worker to support 35 single south Asian, Turkish, Iranian and Middle Eastern women per year, aged 16 to 35, subject to or at risk of domestic and sexual violence and harmful practices ((It is important that harmful practices are understood as forms of VAWG, rooted in gender inequality.)) through refuge provision. The worker provides initial and ongoing support planning and keywork, emotional and practical support and intensive advocacy. Practical and emotional resettlement support is also provided for women and girls at the point of move on from refuge into independent living for six months.

A Senior Counsellor and Group Worker to support 200 women and girls per year through VAWG specialist, trauma-informed counselling in English, Turkish, Kurdish, Farsi, Urdu, Pahari and Hindi (across the team). Women are contacted within 28 days of referral for an intake assessment and counselling is usually offered within 8-12 weeks. The counsellor provides up to 20 one-to-one sessions to women and 8 week psychoeducational group sessions from Ashiana and satellite locations.

She also manages and maintains the waiting list, allocates cases, provides additional support to women and girls between sessions where necessary and connects them with additional support at Ashiana and other local agencies, ensuring aftercare is in place when counselling comes to an end. She ensures the service is operating in line with British Association for Counselling and Psychotherapy (BACP) ethical guidelines, General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and agency protocol and provides peer support to other team members.

Ashiana commissioned Imkaan to conduct an interim evaluation of its NLCF funded provision part-way through the funded project. Primary objectives of the interim evaluation are:

Imkaan takes an intersectional ((‘Intersectionality’ is a prism for understanding how inequality based on different social identities (such as ‘black’, ‘woman’ and ‘refugee’ for example), is overlapping and compounded to form new, specific obstacles for those living at particular intersections.)) approach to data analysis, recognising that Black and minoritised women and girls’ needs, experiences and pathways to support, safety and justice cannot be disentangled without intersectional thinking.

Informed consent and confidentiality: Prior to taking part in the evaluation, all participants were given an information sheet explaining that their participation was voluntary and confidential, and all participants signed an informed consent form before interviews took place which were stored in a locked cupboard. Face-to-face interviews were audio-recorded, and the recordings were destroyed once transcribed.

Survivor wellbeing: Imkaan ensured that Ashiana support workers were available if survivors needed support after the interviews took place. Interviewees were informed that this support was available to them.

Black and minoritised: Unless quoting from an interview or another source, we will use the term ‘Black and minoritised’ throughout this report to speak about those of us often defined in policy terms as Black and ‘minority ethnic’ (BME). This is to acknowledge that ‘minoritisation is an ongoing, active process which marginalises particular groups on the basis of ‘race’, ethnicity and other grounds ... [and] creates and maintains the social, political, economic and other conditions that lead to groups of people being treated and defined as minorities’ (Imkaan, 2018, p7((Imkaan (2018) From Survival to Sustainability. London: Imkaan [pdf document available here]))).

Complex needs: The term ‘complex needs’ is commonly used to describe women who may present to services with a combination of mental ill health, drug and alcohol use. However, throughout the report we use the term to convey the nuances of severe, multiple and co-existing forms of discrimination, stigma and violence that minoritised women are subjected to in society and services - and that specialist ending-VAWG organisations run ‘by and for’ Black and minoritised women have responded to for decades.

Ending VAWG movements have worked actively over the last few decades to improve understanding and responses to the serious and long-term consequences of VAWG and over the last 10 years, the government has taken steps to prioritise the issue, introducing the first strategy to end VAWG in 2009.

The newest ending VAWG strategy was published in March 20164 and a refresh ((HM Government (2016) Ending Violence against Women and Girls: Strategy 2016-2020. London: Crown Copyright [pdf document available here])) was published in March this year.

The strategy lays out government plans to reduce all forms of VAWG and increase reporting, prosecution and conviction by 2020 through four priority areas; prevention, provision of services, partnership working and pursuing perpetrators. The strategy recognises the importance of specialist provision for Black and minoritised women and girls and the importance of smaller, grassroots organisations in supporting survivors with “numerous and complex needs”, acknowledging the challenges such organisations face within the current funding and commissioning landscape.

To that end, the refresh also outlines the government’s commitment to review the National Statement of Expectations (NSE) (2016) ((Home Office (2016) Violence Against Women and Girls: National Statement of Expectations. London: Crown Copyright [link to content here])) which provides a national blueprint for commissioning collaborative, robust and effective VAWG services. The NSE expects local strategies and services to be survivor-centred, locally led and involve, engage and empower communities to help prevent VAWG. Implementation of the NSE is supported by a VAWG commissioning toolkit ((Home Office (2016) Violence Against Women and Girls Services: Supporting Local Commissioning. London: Crown Copyright [link to content here])) which provides key information for commissioning specialist VAWG services. It highlights the importance of equalities-based approaches across every aspect of the commissioning cycle and involving service users and survivors, particularly the most vulnerable, from beginning to end of the commissioning process. The toolkit also highlights the importance of investment in BME-led specialist organisations and cites Ashiana as an example of how investing in such organisations can deliver significant financial savings.

This year, following national consultation, the government also published a draft

Domestic Abuse bill, demonstrating an appetite from the Home Office to bring

8

forward legislation related to VAWG . However, as a general election has now

been announced, the bill has fallen and may or may not be brought forward

((In response to the draft Domestic Abuse Bill, Imkaan published an Alternative Bill which outlines a gendered and intersectional response to VAWG that moves away from a focus on criminal justice and policing, and focuses on sustaining and resourcing expert ‘by and for’ women’s organisations)) depending on which party is elected and what their priorities are for the next parliamentary session.

Both national and regional policy make clear that organisations like Ashiana are a crucial part of addressing violence against women and girls.

The London Mayor’s VAWG strategy 2018-2021 ((Mayor of London (2018) A Safer City for Women and Girls: The London tackling violence against women and girls Strategy 2018-2021. London: Greater London Authority)) outlines key measures to preventing VAWG, tackling perpetrators and protecting and supporting survivors. It recognises the importance of addressing ‘harmful practices’ and acknowledges the needs of those that face significant barriers to reporting violence, including Black and minoritised survivors and those with no recourse to public funds (NRPF). This affirms Ashiana’s importance as an organisation providing critical support to Black and minoritised survivors of VAWG including specialist responses to ‘harmful practices’ and NRPF.

Ashiana was well positioned to deliver the funded project which builds from the long-standing expertise of the organisation. However, while this funding has been critical since local authority funding was diverted from Ashiana in 2015, it doesn’t cover the lost contract value in terms of management and on-costs and Ashiana are currently subsidising these costs.

Recruitment to the counselling and advice services slowed project delivery for a period, particularly within the counselling service which underwent two recruitment processes to secure staff with the appropriate expertise. Staff have now been recruited to all services and delivery is progressing well. Demand for the funded services is high, and the counselling service operates an eight to 12-week waiting list.

Women were referred into Ashiana from a range of agencies including the police, social services, health services, other voluntary sector organisations and a significant number of women self-referred into Ashiana.

Most women accessing Ashiana were aged 21 to 44, defined as heterosexual and had no disability. A small minority of women defined as lesbian, bisexual or questioning and/or identified as having a disability. The majority of those who identified as having a disability reported mental health related disability.

Women came from a diverse range of Asian, African, Caribbean and European ethnicities. In years one and two, the majority of women accessing advice and counselling identified as African and the majority accessing refuge identified as Pakistani. In year three, the majority of women accessing advice identified as East, South East or Other Asian, the majority of women accessing counselling identified as White and Other Ethnicity and the majority of women accessing refuge identified as Indian (See Appendix 1 for a full breakdown of equalities data).

From the dip-sample and broader evaluation activities it was evident that women accessing Ashiana were subject to multiple forms of violence over long

periods of time. Violence was constant and cumulative, and often consisted of physical, sexual, psychological and/or economic violence from multiple perpetrators. Women had been forced into domestic servitude, belittled, humiliated, threatened, tracked, entrapped and were ostracised in extended family and community spaces.

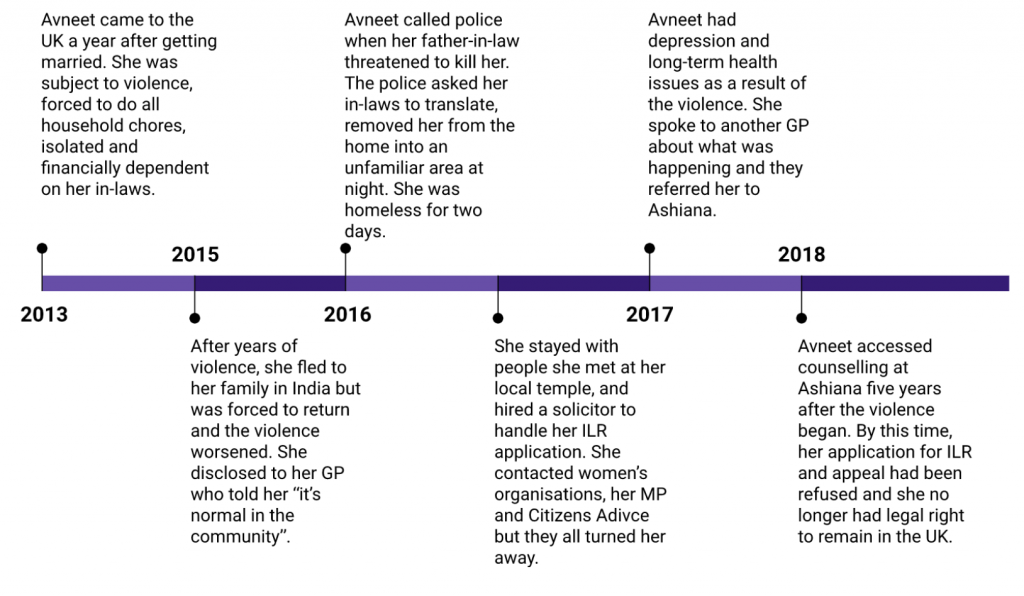

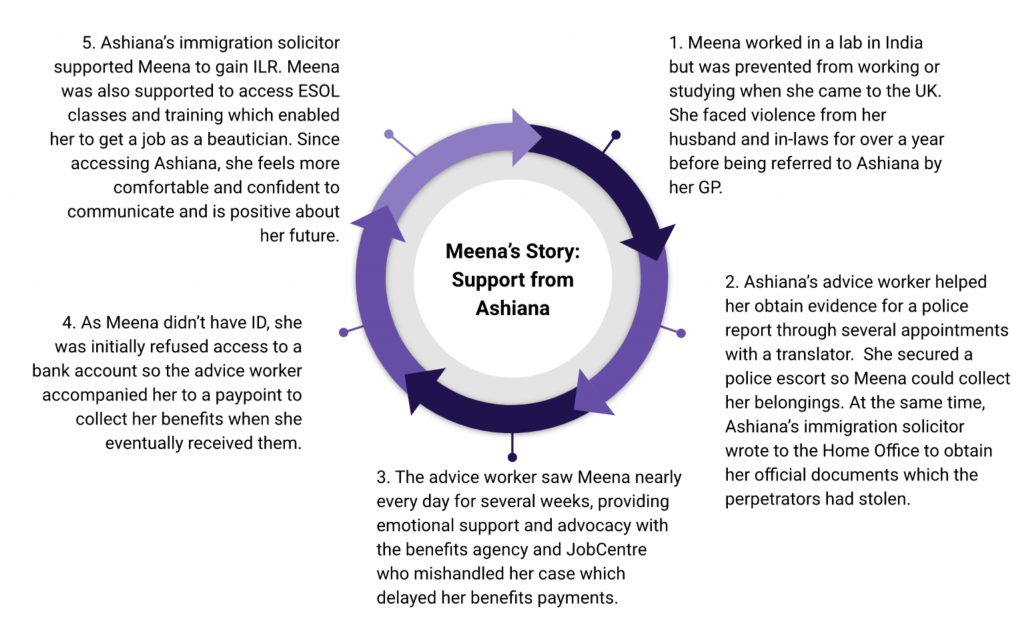

Some women had lived in the United Kingdom (UK) for a short period of time and were confronted with an unfamiliar system, language, people and ways of life when they arrived. Some had been studying in higher education or had a career before moving to the UK where they had no support network and were financially dependent on their violent partner and in-laws. Many women were pressured to remain in the violent relationship and were disowned or received death threats if they attempted to leave. Violence impeded women’s freedom of movement in the UK, their ability to return to another country, and whether they felt able to escape the violent context at all.

Women were navigating a complicated and often discriminatory statutory system. Some women sought support from multiple agencies before being referred to Ashiana and had been poorly treated, turned away and/or their support needs left unidentified, by several agencies. They were forced to tell their stories multiple times, prove and re-prove their experiences, and were often met with an attitude of disbelief or judgement by police, social workers, housing, GPs, courts and Home Office staff. Delays and inconsistencies in statutory processes had prevented women getting the support they needed when they needed it, and some were forced to return to situations of violence when they had sought help to no avail. Poor handling of cases prior to accessing Ashiana had compromised women’s physical safety and mental wellbeing.

Many women had a precarious immigration status and NRPF, requiring Ashiana’s support to regularise their status. Visa status was often exploited by perpetrators, used to coerce and control women and prevent them from seeking help in the first place. Women navigating the immigration system were met with poor responses, inconsistent processes and long wait times for the outcome of applications.

Whether ‘newly arrived’ or born in the UK, women accessing Ashiana were navigating the system in the context of patriarchy, racism and xenophobia at individual, institutional and societal levels and were grappling with the sense of un-belonging, loneliness and dislocation that this can bring.

Complex issues and systemic discrimination intersected with women’s experiences of violence and trauma which had a cumulative impact on independence, self-esteem and confidence. A significant number of women had depression and/or suicidal ideation, flashbacks, blackouts and anxiety following violence and women’s mental wellbeing fluctuated throughout their engagement with Ashiana, often linked to how their cases were progressing through immigration and statutory systems. Some women also had long-term physical health conditions as a result of the violence. Within this context, Ashiana’s support provides a critical lifeline to women and girls who come through the service.

Significant progress has been made towards project outputs and outcomes across the service areas and the target for number of women in refuge was exceeded. While the counselling service has not met planned targets, this is because the organisation underwent two lengthy recruitment rounds since the funding began. It is expected that outputs will pick up now that the service is more stable. While the advice service is just under target, again, recruitment for the service took some time and targets should pick up as the project progresses over the next two years.

| Output | Year 1 actual | Year 2 actual | Year 3 actual | Total target to date | Total actual |

| 1 counsellor to support 200 women and girls a year | 73 | 76 | 127 | 600 | 276 |

| 1 senior specialist advice worker to support 250 women and girls a year | 299 | 206 | 212 | 750 | 717 |

| 1 housing support worker to support 35 women a year | 40 | 46 | 40 | 105 | 126 |

Annual monitoring data demonstrates that all change indicators have been met and the majority have been exceeded over years 1 to 3 of the NLCF funded project. In terms of change indicators for outcome 5, while women accessing refuge provide regular feedback and input into the service, it has proven more difficult to gather feedback from women in the advice and counselling services who access support for a much shorter period of time and are more likely to exit informally.

Ashiana has overachieved on NLCF project outcomes within a context of loss of local authority funding which means they are currently subsidising management and on-costs (that were previously funded through the local authority). Understandably, this is not a situation that is sustainable for the organisation.

| Change Indicators | Year 1 actual | Year 2 actual | Year 3 actual | Total target to date | Total actual |

| Outcome 1: Increased provision of holistic, person-centred approaches for women and girls at risk (women and girls are supported to be safe) | |||||

| 35 women access specialist safe housing | 40 | 46 | 40 | 105 | 126 |

| 80% of women and girls report a reduction in abuse | 80% | 87% | 81% | 81% | 83% |

| Outcome 2: Women & Girls have improved access to support services | |||||

| 200 women access specialist support services i.e. counselling, solicitors | 318 | 256 | 209 | 600 | 783 |

| 50 women and girls access translation and interpretation | 65 | 66 | 72 | 150 | 203 |

| Outcome 3: Increased role and voice for women and girls in co-producing services (women and girls will be involved in the design and delivery of the project) | |||||

| 6 service users participate in the tenant representative forum | 6 | 6 | 6 | 18 | 18 |

| 20 women and girls attend strategic planning events | 40 | 46 | 40 | 60 | 126 |

| Outcome 4: A greater number of women and girls are supported through the provision of improved specialist support (women have improved lives through specialist intervention) |

| Change Indicators | Year 1 actual | Year 2 actual | Year 3 actual | Total target to date | Total actual |

| 100 women access specialist legal advice | 158 | 150 | 97 | 300 | 405 |

| 80% of service users report increased confidence | 80% | 82% | 88% | 88% | 89% |

| Outcome 5: Better quality of evidence for what works in empowering women and girls (improved systems for documenting and sharing learnings from project) | |||||

| 70% of service users complete surveys and attend focus groups | All refuges residents complete regular evaluation but this is harder for advice and counselling clients who engage with support for a shorter period. | ||||

| Stakeholder interviews conducted with at least 5 partner services, annual shared learning event - seminar or roundtable | 5 stakeholder interviews were conducted as part of the evaluation. The shared learning event will be hosted at the end of the project. |

The effectiveness of the NLCF funded package of support was underpinned by several key features of Ashiana’s approach and practice. These themes are presented below, with reference to how they link to the achievement of NLCF project outcomes and the added value they bring to the funded project. The following themes relate specifically to the achievement of outcomes 1, 2 and 4 which are:

Outcome 1: Increased provision of holistic, person-centred approaches for women and girls at risk (women and girls are supported to be safe)

Outcome 2: Women & Girls have improved access to support services

Outcome 4: A greater number of women and girls are supported through the provision of improved specialist support (women have improved lives through specialist intervention)

Ashiana is led and staffed ‘by and for’ Black and minoritised women and provides a space of safety and belonging for women who encounter multiple, intersecting inequalities which shape their experiences of violence and access to safety/support. It was very clear that staff had expert understanding of the needs and experiences of minoritised women and service delivery was rooted in a sophisticated, intersectional response to VAWG within a wider context of systemic inequality. Staff were relatable and built trust and ‘sisterhood’ with survivors, supporting and advocating for women from a place of understanding and connection which survivors felt was distinct to mainstream provision. The importance of this structure should not be underestimated. 82% of survivors in the dip-sample stated they had a preference for a ‘by and for’ refuge, and it was evident that Ashiana’s by and for approach was critical to women’s engagement with the service.

She always treats us not like clients, she says I am like you, don’t worry”

Survivor

I feel like someone is here to listen to me. It’s totally different [to other services] ... they are really helpful ... I tried a lot to get help from other people ... but no one gives me any response

Survivor

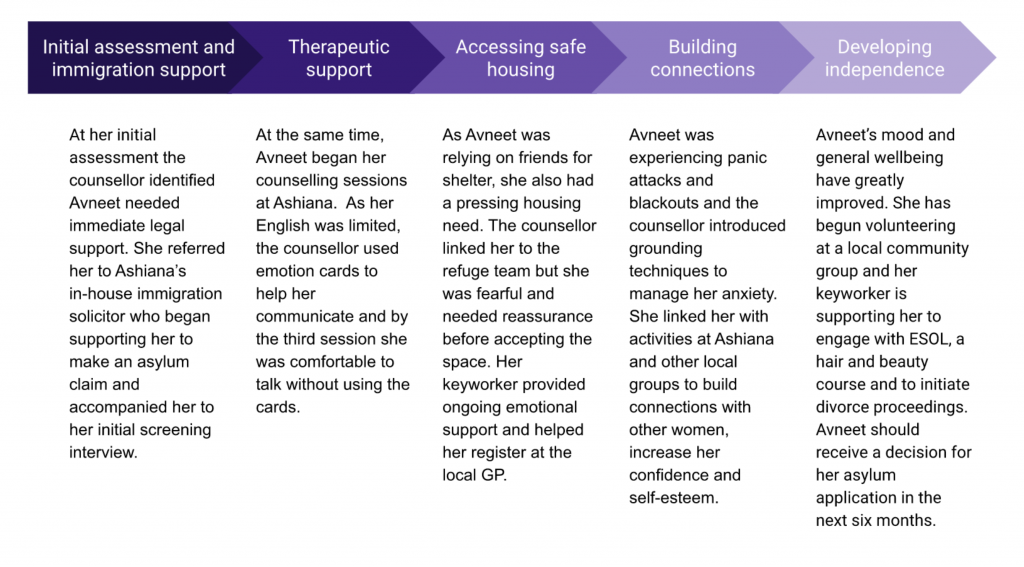

Staff actively challenged the exclusion minoritised women often face in society, by de-stigmatising their experiences and believing their stories. For example, ‘immigration issues’ are often problematised and result in women being turned away from mainstream services. By contrast, Ashiana recognise the criticality of regularising immigration status in building women’s mental health, safety, economic stability and independence. They responded to immigration concerns as one of the myriad issues women presented with and this support was as central to Ashiana’s service as their response to VAWG itself. This approach validated women’s journeys and allowed them to show up as who they were, and the importance of this specialism was reinforced by staff and stakeholders.

Having an understanding of some of the barriers that our client group potentially going through ... Having that environment full of other BME women, that really contributes to create that sisterhood.

Worker

Without BME specialist organisations it would be very difficult for ethnic minorities to come forward, report, seek help, they will suffer more.

Stakeholder

Ashiana’s current package of support is built on years of development of specialist services that address gaps in support for particularly marginalised women who are often turned away from mainstream provision. For example, Ashiana provide dedicated refuge spaces and a weekly subsistence allowance for women with NRPF who are prevented from accessing benefits and are routinely turned away from generic services who are not funded to support them. Ashiana also provide an in-house immigration solicitor to support immigration applications. 25% of women from the dip-sample were accessing Ashiana’s in-house immigration advice alongside NLCF funded support. Regularising immigration status is hugely important in supporting women’s wellbeing and independence and adds significant value to the NLCF funded provision.

Similarly, Ashiana are one of the very few services that provide a specialist response to girls/young women aged 16-17, including dedicated refuges for those at risk of forced marriage. Workers have an expert understanding of forced marriage and young women’s specific support needs, given that they may never have lived independently, or managed a tenancy or their own finances before. They provide intensive emotional and practical support and advocacy to younger women who often fall through the gaps as refuges tend to house women from 18 onwards.

Ashiana continues to improve their knowledge and skills where necessary to address gaps in services for particular groups of minoritised women. For example, after recognising that low numbers of LBTQ women access their services, over the last two years, they have engaged in partnership with specialist women’s and LGBT organisations to build links, access training and develop learning to ensure they are able to respond/provide support for LBTQ women at risk of violence with NRPF. Though this is a work in progress, some partners have already begun to see an increase in disclosures and feel better equipped to support these groups of women.

The project has been very good as a partnership and we have seen some women come forward. There is still work to do, but we have had some disclosures.

Stakeholder

These areas of expertise add significant value to the NLCF funded contract and improve access to specialist support for women who may otherwise have nowhere to turn, directly linking to the achievement of outcomes 1, 2 and 4.

As highlighted earlier, most women come to Ashiana with multiple, intersecting support needs and Ashiana routinely responds to complex ((Please see Terminology section for a note on the term ‘complex needs’.)) cases through a range of support, often from several services. This was evidenced by dip-sample data which showed that 68% of women had multiple, co-occurring needs, and 63% had accessed more than one service at Ashiana to address those needs. The table below demonstrates the percentage of women in the dip-sample taken from each NLCF funded service that were also accessing other services at Ashiana:

| Also accessing refuge | Also accessing advice | Also accessing counselling | Also accessing other Ashiana services | |

| Refuge cases (n=12) | 33% | 42% | 92% | |

| Advice cases (n=14) | 7% | 21% | 14% | |

| Counselling cases (n=14) | 7% | 43% | 21% |

As the table shows, women accessing the NLCF funded services were often accessing a range of support from Ashiana to support them with a range of needs. The vast majority of women in refuge were accessing a range of other support at Ashiana, and a significant proportion of women accessing counselling were also accessing advice alongside additional Ashiana services. The fact that women had access to support beyond the funded package represents added value to the NLCF contract.

The nature of Ashiana’s person-centred, holistic support was central to women’s engagement and progression through the service and contributes to progress towards outcomes 1 and 4. Staff worked at women’s paces and dedicated time to build relationships with women, prioritising their safety while working flexibly around their choices, without penalising or pressuring them to engage. Women undertook significant personal journeys at Ashiana to gain a sense of safety, stability and hope and were gradually supported to rebuild their ‘sense of self’ following violence and trauma which had eroded their confidence, self-esteem and mental health. They were supported to make informed choices, have their voices heard, pursue their passions, fight for their rights and build support networks. It was evident that staff were deeply committed to women, ‘travel the journey’ with them and provide a consistent approach at a time when their life can feel chaotic and out of their control.

When everything else in her life was falling apart, we were consistently the same with her, she got that same level of support.

Staff member

The NLCF funded services seamlessly connected to Ashiana’s wider provision, and the joined-up nature of support repeatedly came up as a distinctive feature of Ashiana’s approach which ensured a collaborative, holistic response to women’s needs. It was clear that a strong team approach existed, evidenced by staff who felt they could easily follow-up on cases, request support from each other and were assured that cases were being handled appropriately by other members of the team:

It makes a major difference knowing that I have in-house staff I can refer to very quickly, I know it will be prioritised and they will action but more importantly, hearing from some of the experiences of clients with NRPF and the bad experiences they had with solicitors making immigration applications ... I know that the client is in safe hands, that her case will be dealt with thoroughly, whether it’s a negative outcome or not, I know that the solicitor will be doing her best

Staff member

Linking women to multiple in-house services also increased the accessibility of specialist services to women who were able to see several workers in the same location on the same day. This meant women did not have to retell their stories multiple times and were familiar with multiple staff who could inform them on the progress of their cases and directly respond to their needs. This approach provided stability and security for women which supported their mental health at a time that was extremely stressful. If one staff member was aware that a survivor was feeling particularly low, or required more intensive support, this was quickly communicated to relevant staff and any safeguarding concerns were efficiently responded to.

“Initially, she wouldn’t get out of the house ... Now she was making friends, going to places on the bus, building relationships and taking the initiative to go to a centre to volunteer, do arts, crafts, walking, making time for herself, recognising what works for her and what she needs” (Worker)

"my experience at Ashiana's counselling was great as it came to me at the right time when I was dealing with the worst situations. It helped me calm down and be positive. [the counsellor] was wonderful and made me feel comfortable so that I would tell her everything. Overall it was a really great experience. I will miss [the counsellor] and the sessions too." (Survivor)

The dip-sample data demonstrated that many women presented to Ashiana with mental health issues including depression, anxiety and self-harm, linked to the violence they were subject to.

Research shows that mainstream mental health provision has high thresholds, long waiting lists, is often provided in English and lacks understanding of the impact of violence on women’s lives ((Imkaan, Positively UK and Rape Crisis England and Wales (2016) Women's Mental Health and Wellbeing: Access to and quality of mental health services. London: Women's Health and Equality Consortium.)) (Imkaan et al. 2016) . The NLCF funded VAWG specialist, trauma-informed counselling provision was a critical component of support contributing to the achievement of outcomes 1, 2 and 4.

The counsellor had an excellent understanding of VAWG, and the impact of intersecting inequalities on minoritised women’s journeys and experiences which meant that women’s experiences of violence were understood and held in the counselling room. The counsellor created space for women to build self-esteem, identify the roots and impacts of their emotions and triggers, develop grounding techniques, stimulate positive thinking and encourage self-care. There was also space for women to talk through practical aspects of their cases, such as the progression of cases through the immigration system, which was sometimes the most concerning issue for women at a particular point in time. The counsellor recognised the stigma attached to counselling and took time to build rapport with women, allowing them to engage at their own pace. The counsellor not only provided specialist therapeutic support, but also recognised the importance of practical assistance including access to refuge, or connecting with other women, and worked pragmatically to ensure this support was in place.

Outside of the one-to-one counselling space, all frontline staff delivered an element of therapeutic support to women as ongoing emotional support was routinely provided in refuge and advice services to help prevent deterioration of mental health and wellbeing. Additional groups and activities including a gardening project and song-writing workshops enabled women to access peer support, connect with each other, gain a sense of belonging and reduce isolation (which can exacerbate poor mental health). It was imperative for women that their emotional needs were met alongside practical issues, and Ashiana’s specialist therapeutic approach contributed greatly to women’s recovery and healing.

A key component of Ashiana’s specialist support is intensive advocacy to challenge systemic discrimination and to ensure women are appropriately supported by statutory agencies, supporting progression towards outcomes 2 and 4. In 58% of cases from the dip-sample, Ashiana had advocated on behalf of women with other agencies including social services, housing, JobCentres, the police, GPs and solicitors. It was clear that staff supported women to engage with statutory and mainstream agencies “from beginning to end”, and the evaluation found many instances of staff accompanying women to appointments with statutory agencies, courts, banks, solicitors, GPs and the Home Office reporting centre, which was critically important until women had built confidence to navigate the system themselves. Ashiana’s intensive advocacy directly challenged inappropriate decisions or practices among mainstream agencies, ensured women’s rights were upheld, secured evidence to support immigration applications and supported women to access benefits, healthcare and education.

Case study

Noelle was discriminated against by a staff member at the local JobCentre, who would tell her he was going to sanction her claim every week without reason. He told her she was not doing enough to look for a job and when she explained that she was exempt under the DV easement he asked why she was living in a refuge, dismissed her experiences of violence and told her she should be looking for work. Ashiana made a formal complaint and were invited to meet with the centre’s manager. Ashiana worked to build a positive relationship with the JobCentre and delivered several trainings to the staff team which encouraged a shift in attitudes and responses across the organisation. The JobCentre have since changed their processes and now have an allocated DV lead who allocates each client with an advisor accordingly.

Collaborative work to improve support for Black and minoritised women and girls

Ashiana is really important to us, does a lot considering it’s a small organisation ... those particular clients need really specific advice and support and Ashiana enables us to offer that rather than just saying here’s a link to someone’s website ... Without it, I’m not sure we would be able to offer sufficient advice and I’m certain the local authority wouldn’t eithe

Stakeholder

They’re a good local organisation in East London that works very specifically with BME groups and they’ve had a long history of providing services in that neck of the woods ... they have that specialism, they’re led ‘by and for’, they’re part of the community in East London ... we’ve got a mix of specialisms and working together, it enhances what women are offered ... we’re able to reach women better by working together

Stakeholder

Ashiana’s commitment to collaboration and building strong partnerships with other agencies was key to improving external responses to women and girls and ensuring appropriate support was in place for women beyond Ashiana’s provision. Ashiana have built a reputation as a supportive and highly credible organisation among external stakeholders who recognised the value of their expertise and often reached out for help to improve their practice.

It was evident that Ashiana had developed long-term, positive working relationships ((Including women’s organisations, community-based services, police, social services, GPs, solicitors, schools, colleges, children’s centres, job centres, housing, banks, supermarkets.)) and formal partnerships with a range of voluntary and statutory agencies, some that had similar and some that had very different ideologies or political underpinnings. For example, Ashiana develops partnerships with other specialist agencies to address issues of shared concern, enhance services for minoritised women, provide mutual support, increase referral pathways, shift policy and practice and increase credibility and access to funding for specialist services. Again, this work adds value to the NLCF contract, ensuring that Ashiana and the wider sector are sustained, and specialist support remains available for minoritised women. Additionally, Ashiana has developed strong working relationships with local statutory agencies to help improve their practice, which supports the achievement of NLCF outcomes 1, 2 and 4.

Case Study

A London-based homelessness prevention project (who heard about Ashiana through one of the partnerships they are involved in) contacted Ashiana for support when they recognised that a significant number of minoritised women subject to violence were coming through their service, and that they did not have the skills to support them. The project has now established a referral pathway to Ashiana for women in need of specialist support and regularly accesses telephone advice from Ashiana. Ashiana also provided in-kind training to project staff, to improve their understanding and response to the issues which enabled them to spread this knowledge to other mainstream agencies including the local authority. The project has invited Ashiana to sit on a homelessness partnership, to represent the voices of minoritised women subject to violence and improve their access to support.

The following themes are related to the achievement of outcomes 3 and 5 which are:

Outcome 3: Increased role and voice for women and girls in co-producing services (women and girls will be involved in the design and delivery of the project)

Outcome 5: Better quality of evidence for what works in empowering women and girls (improved systems for documenting and sharing learnings from the project)

It was evident that Ashiana has begun to introduce mechanisms that give women a critical voice in co-producing refuge policy and practice to ensure the service meets their needs and to enable women to see how their voices can influence change. Staff hold regular house meetings and quarterly meetings for women across all three refuges and in the last six years, Ashiana has introduced tenant reps for each refuge who regularly meet with the service user involvement lead in housing services. Women were given the opportunity to co- produce a communal living policy based on their views and experiences. Tenant reps have also raised women’s views to Ashiana staff, resulting in specific changes including access to Wi-Fi in refuge, updates to the confidentiality policy and house rules. This is central to the achievement of outcome 3. As the project continues, it would be beneficial to think through the approach to co-production, how this can be meaningfully embedded within advice and counselling service design and delivery, and for the final evaluation it would be useful to hear directly from women about their experiences of co-production.

Alongside developing mechanisms for co-production, Ashiana has also facilitated direct engagement between survivors and decision makers which has increased women’s understanding of decision-making processes and increased understanding in political spaces of the importance of Ashiana’s services:

Case study

A Baroness requested to visit an Ashiana refuge following a recommendation from Women’s Aid. Ashiana facilitated the visit, introduced the Baroness to refuge residents, provided case studies and outlined the day- to-day support to give her an understanding of the importance and distinctiveness of ‘by and for’ provision. She then took part in a debate on domestic violence in the House of Commons where she spoke highly of Ashiana and following this, Ashiana’s refuge residents were invited to visit the House of Commons and House of Lords, giving them an understanding of the law-making process. The Baroness' office has since been in touch to explain how women can sit in on debates, which staff will take forward with women.

Ashiana has implemented systems which provide good quality evidence of the effectiveness of their work. They have an online case management system (Lamplight/Synthesis) that holds quality data on the women who come through their service. Ashiana also have the benefit of a dedicated staff member who leads on monitoring and evaluation, develops detailed monitoring reports for funders and regularly updates the case management system to ensure it is fit for purpose. She provides yearly training for staff and is in the process of developing a booklet to support staff to input data which has been a continued challenge to balance with frontline service delivery. While the system holds rich data, it has been challenging for management staff to allocate time to use data strategically (beyond funder requirements), to understand emerging issues and inform future developments.

NLCF funded provision is monitored through evaluation forms, CORE 34 forms for the counselling service, consultation with women in refuge via regular house meetings and support groups centred on themes women want to discuss. However, gathering feedback from women in the counselling and advice services is sometimes challenging as women move through these services more quickly and may be more likely to disengage informally - without completing an evaluation or CORE 34 form. Staff are already thinking about introducing a review after six weeks of counselling and as the project progresses it would be worth considering design and implementation of mechanisms to gather regular feedback from women, or a sample of women who access advice and counselling provision - to inform future service development.

The project is clearly progressing well, all change indicators have been met or exceeded and Ashiana are working hard to meet target outputs. Given the complexity of cases the organisation is dealing with, there are a few issues to consider in terms of women’s support needs.

Navigating and responding to systemic inequality and inappropriate statutory responses is an ongoing challenge for Ashiana that lengthens cases and puts women’s recovery on hold. Women with NRPF often need to stay in refuge longer while they wait for immigration/asylum decisions which can take years and the advice service often struggles to find external support for single women with no recourse to public funds who are not housed in the refuge.

Securing safe, appropriate move-on accommodation in the local area (where women have established support networks) is an ongoing issue for women ready to leave refuge, as there is no available local authority housing stock. Again, this can result in women remaining in refuge for longer periods of time and in need of additional support with budgeting to prepare them for the large deposits they will need to secure private housing.

Ashiana often must make statutory agencies aware of their responsibilities to women, particularly housing and social services whose responses are inconsistent from borough to borough. Staff are grappling with insufficient responses and lack of specialist services for young women, particularly for those subject to sexual exploitation. Ashiana often deliver intensive advocacy to ensure young women’s needs are communicated and appropriately addressed

by social services and it can take longer to achieve an outcome for this client group. Given the insufficient responses from statutory agencies, Ashiana can end up “holding the risk” for long periods of time while they are securing additional support for women and girls (particularly those who come through the advice service and are not housed in refuge).

In terms of women’s support needs, it is evident that cuts to legal aid and restrictive criteria for accessing legal aid have made it more difficult for women to access legal advice in relation to family and/or criminal law. Ashiana rely on sourcing external solicitors which is costly and means women ineligible for legal aid cannot easily access legal representation. Some solicitors are reluctant to take on legal aid clients in case women do not meet the criteria and they are left with the costs. In one instance where a survivor needed a non-molestation order, the lengthy process of proving eligibility for legal aid meant that a non- molestation order was no longer relevant by the time she had secured legal aid.

Staff also highlighted a specific difficulty for women with pre-nursery age children in accessing the counselling service due to lack of childcare. Given the specialist nature of this therapeutic support (which is very scarce outside of Ashiana), it would be worth considering seeking funds for a play therapist to support children to enable mothers to access counselling.

NLCF outcomes data indicates high demand for interpreting services which were required by 53 more women than anticipated over years one to three. While it is difficult for smaller organisations to provide access to interpreting as this is not funded as a core cost, Ashiana does provide access to an external telephone- based interpreting service to ensure survivors with language support needs have access to support and advice. That said, staff felt that women would value quality, face-to-face interpreting services which would make it easier for women to connect with the interpreter, relay personal and difficult experiences of violence and ensure the nuances of the cases are accurately translated. This is likely to be a national issue and it would be useful for Ashiana to engage with other ‘by and for’ organisations and Imkaan to consider developing a pool of interpreters for the sector.

In terms of staff and organisational needs, counselling and refuge staff have access to group clinical supervision and Ashiana recently secured additional time-limited funding from the NLCF for a staff wellbeing project, providing workshops on self-care techniques. Given the complexity of cases staff are dealing with, it would be valuable to sustain wellbeing support on a long-term basis, to support staff to deal with secondary trauma.

In terms of evidencing the impact of their work, Ashiana has a robust case management system in place that allows the organisation to capture good data on women’s journeys through the service. However, it can be challenging to gather feedback from women who access counselling or advice, as they move through the service more quickly than those in refuge and are more likely to exit informally. It would be useful to develop mechanisms to capture feedback from a sample of women in advice and counselling to support Ashiana to better understand how these services are working for women and to inform service development. It would also be useful to introduce a distance-travelled form across all NLCF funded services to better demonstrate women’s journeys through the service for the final evaluation.

The case management system also allows Ashiana to gather equalities data from all women who come through the service. In year 3, reports on equalities data shifted in line with the Office of National Statistics equalities categories and funder reporting requirements. It is understandable that reporting will be based on the level of data funders require, however Ashiana should continue to capture detailed equalities data, and review this internally, to ensure accurate assessment of which women are engaging with the service and to identify any specific gaps across the protected characteristics.

Finally, while Ashiana is delivering a high-quality and essential service, the organisation is also operating with reduced funds as the NLCF contract which replaced the local authority contract does not cover infrastructure costs which are currently subsidised by Ashiana. Given this, it is important that Ashiana continues to diversify funding streams as the project continues.

There is no doubt that the NLCF funded project is progressing well, and Ashiana is overachieving on most indicators of change despite delivering in a context of reduced funding. It is evident that Ashiana’s ‘by and for’ approach, VAWG specialist, trauma-informed therapeutic approach and active response to systemic inequality were central to the success of the project and women’s engagement with the service. The provision of holistic, wrap-around support and advocacy to women with multiple, complex needs enabled most women to access the support they needed under one roof, increasing women’s access to specialist support and safety. Ashiana’s specialist responses to young women at risk of forced marriage and women with no recourse to public funds, as well as their collaborative approach to the work, added significant value to the funded package of support. Overall, NLCF funding has enabled Ashiana to sustain and develop critical and life-saving services for Black and minoritised women and girls who may otherwise have very limited access to help and support.

There are several considerations for Ashiana to take forward as the project continues and the following recommendations have been developed based on the findings of the evaluation:

| Consideration | Recommendation |

| For survivors | |

| Reduced access to family/criminal legal advice as a result of cuts to legal aid and restrictive eligibility criteria | Consider seeking funds to develop in-house legal advice based on Ashiana’s existing immigration advice service |

| Women with pre-school age children who do not have access to childcare have difficulty accessing Ashiana’s counselling service | Consider seeking funds for a play therapist to work with pre-nursery age children to enable mothers to access the counselling service at the same time |

| Difficulty accessing face-to- face, high quality interpreting provision | As this is likely to be a national issue, it would be useful for Ashiana to engage with other ‘by and for’ organisations and Imkaan, to consider developing a pool of interpreters for the sector |

| For Ashiana |

| Limited wellbeing support for staff dealing with complex cases daily (beyond clinical supervision for some staff) | RecomInvest in training for all staff to support them to deal with secondary traumamendation |

| Difficulty gathering feedback from women who exit the service quickly or informally (particularly those that access counselling and/or advice) | Develop processes and mechanisms to gather feedback prior to women exiting the service, and implement a distance travelled tool with a sample of women across NLCF funded services to help demonstrate women’s journeys through the service to inform the final evaluation. Imkaan can support the development of a distance travelled tool. |

| Embedding co-production within advice and counselling services and evidencing the impact of co-production | Think through co-production approach as the project progresses and map the impact of this to inform the final evaluation. Imkaan could support the development of a template to better evidence co-production for the final evaluation. |

| Difficulty evidencing outcome 5 ‘Better quality of evidence for what works in empowering women and girls’ | Think through ways of collecting data/evidence for outcome 5 in order to document and share learnings from the project. For example, Ashiana could embed space in team meetings to discuss (and minute) practice, what worked and lessons learned which could inform future shared learning events |

| Operating with reduced funding | Continue to diversify funding streams as the project progresses |

In years 1 and 2, the majority of women accessing advice and counselling were aged over 30, with a significant minority aged 21-30. Smaller numbers were aged 18-20 and up to 17. In refuge, the majority of women were aged 21-30, a significant minority were over 30, again with smaller numbers aged 18-20 and up to 17:

| Age | Advice (year 1&2) | Counselling (year 1&2) | Refuge (year 1&2) |

| Up to 17 | 1.2% | - | 4.7% |

| 18-20 | 8.1% | 2.7% | 12.8% |

| 21-30 | 33.9% | 31.5% | 58.1% |

| Over 30 | 44.8% | 54.4% | 22.1% |

| Prefer not to say | 12.1% | 11.4% | 2.3% |

In year 3, equalities monitoring categories were changed in line with the Office of National Statistics and Ashiana’s reporting requirements for funders. Under the new categories, the majority of women accessing advice were aged 35-44, the majority of women accessing counselling were aged 34 and under, and all those who provided information on age in refuge were aged under 44:

| Age | Advice (year 3) | Counselling (year 3) | Refuge (year 3) |

| 24 and under | 7% | 33% (34 and under) | 79.5% (44 years and under) |

| 25-34 | 25% | ||

| 35-44 | 49.5% | 22% | |

| 45-54 | - | 22% | - |

| Prefer not to say | 18.4% | 22.8% | 20.5% |

For those who provided information about their sexuality, the vast majority defined as heterosexual, less than 1% of women in each service defined as lesbian and a smaller number identified as questioning or bisexual. The remainder preferred not to disclose their sexuality:

| Sexuality | Advice | Counselling | Refuge |

| Heterosexual | 87.1% | 77.6% | 87.9% |

| Lesbian | 0.3% | 0.5% | 0.8% |

| Questioning | 0.1% | - | - |

| Bisexual | - | 0.5% | - |

| Prefer not to say | 12.5% | 21.4% | 11.3% |

The majority of women did not identify as having a disability and the majority of those who did disclose disabilities were related to mental health. Smaller numbers identified as having hearing impairment, learning difficulty, mobility issues or visual impairment:

| Disability | Advice (year 1&2) | Counselling (year 1&2) | Refuge (year 1&2) |

| Hearing impairment | 0.8% | 2% | - |

| Learning difficulty | 0.6% | 1.4% | - |

| Mental health | 5% | 16.3% | 5.8% |

| Mobility | 1% | 1.4% | - |

| None | 82.8% | 61.2% | 88.4% |

| Prefer not to say | 9.7% | 17% | 4.7% |

| Visual impairment | 0.2% | 0.7% | - |

| Other disability | - | - | 1.2% |

Again, in year 3, equalities monitoring categories changed and captured only mental health disabilities:

| Disability | Advice (year 3) | Counselling (year 3) | Refuge (year 3) |

| Mental health | 3.9% | 8.7% | - |

| Not disabled | 76.5% | 55.6% | 81.6% |

| Prefer not to say | 19.6% | 35.7% | 18.4% |

In years 1 and 2, the majority of women accessing advice and counselling defined as African (27.2% and 15.1% respectively) and the majority of women accessing refuge defined as Pakistani (30.2%). Smaller numbers were accessing Ashiana from a diverse range of Middle Asian, African, Caribbean, European and Middle Eastern ethnicities.

| Ethnicity | Advice (year 1&2) | Counselling (year 1&2) | Refuge (year 1&2) |

| Afghani | 4.7% | - | 4.7% |

| African | 27.2% | 15.1 | - |

| Albanian | 1.8% | 1.9% | - |

| Algerian | 1.2% | - | - |

| Arab | 1.2% | - | 1.2% |

| Asian | 4.1% | 11.3% | - |

| Bangladeshi | - | - | 15.1% |

| Black British African | 10.7% | 13.2% | - |

| Ethnicity. cont. | Advice (year 1&2) | Counselling (year 1&2) | Refuge (year 1&2) |

| Black British Caribbean | 2.4% | 9.4% | - |

| Black British Other | 0.6% | 7.5% | - |

| Chinese | 1.8% | 1.9% | - |

| Eastern European | 4.7% | 3.8% | - |

| Filipino | 0.6% | - | - |

| Korean | 0.6% | - | - |

| Indian | - | - | 19.8% |

| Iranian | 1.2% | - | 5.8% |

| Iraqi | 1.8% | 1.9% | 1.2% |

| Mauritian | 1.2% | - | - |

| Mixed Other | 1.2% | - | - |

| Mixed White & Black African | 1.2% | - | - |

| Mixed White & Black Caribbean | 1.2% | 1.9% | - |

| Moroccan | 3.6% | 1.9% | 3.5% |

| Other | 5.9% | 13.2% | 1.2% |

| Other Asian | 5.3% | 3.8% | - |

| Ethnicity. cont. | Advice (year 1&2) | Counselling (year 1&2) | Refuge (year 1&2) |

| Pakistani | - | - | 30.2% |

| Portuguese | 1.2% | - | - |

| Romanian | 1.8% | - | - |

| Somalian | 2.4% | - | - |

| Sri Lankan | - | 1.9% | 2.3% |

| Thai | 0.6% | - | - |

| Turkish | 7.1% | 9.4% | 10.5% |

| Ugandan | 0.6% | - | - |

| White Other | 2.4% | 1.9% | - |

| Prefer not to say | - | - | 4.7% |

In year 3, the majority of women accessing advice wear East, South East or Other Asian, the majority of women accessing counselling defined as White and Other Ethnicity and the majority of women accessing refuge defined as Indian.

| Ethnicity | Advice (year 3) | Counselling (year 3) | Refuge (year 3) |

| African | - | 7.3% | - |

| Asian | - | 5.5% | - |

| Asian British | 3.8% | - | - |

| Bangladeshi | 12.3% | 9.1% | - |

| Black British and Black African | 12.3% | 9.1% | - |

| East, South East and Other Asian | 14.2% | - | - |

| European | 3.8% | - | - |

| Indian | 10.4% | 13.6% | 29.4% |

| Middle Eastern and North African | 7.5% | - | 26.5% |

| Mixed Ethnicity | 2.8% | - | - |

| Pakistani | 16% | 19.1% | 20.6% |

| White & Other Ethnicity | 2.8% | 20.9% | - |

| Prefer not to say | 14.2% | 15.5% | 23.5% |